The first time I met my fifth father, he said to me, “You look just like Barbara Streisand.” I asked him if he liked Barbara Streisand and he said he did. I was flattered at the comparison, for several reasons: her beautiful eyes, lovely voice and gorgeous hands. He did list some of these features, but mostly I was flattered because it was an affirmation of all I had come to believe about myself – that my father (biological) was Jewish. Many people have corrected me when I mention my belief. They pontificate over the Code of Jewish Law and tell me I can’t claim to be a Jew unless my mother is a Jew. I don’t think Hitler quibbled over such details.

Anyway.

When I was a young girl running home to watch Dark Shadows, I knew deep down inside that something was different about me. I didn’t look like my siblings and didn’t behave like them and our interests were totally different. My sisters were good at sports and gregarious people who had many friends and loved to be with people. I preferred a good book, writing short stories and poetry and was painfully shy in classrooms and crowds.

Therefore, when I discovered the television program Dark Shadows, I identified strongly with Victoria Winters and hoped one day she’d find out the truth about her origins. Soon though, Dark Shadows became too campy and silly for me and I moved on. Even back then the simpering sweetness of her character was beginning to annoy me, and I’ve since learned the actor who played the original Victoria Winters also disliked the insipidness of her television persona.

I must begin at the beginning – the day I first learned about my biological father. It was the summer of 1972; I had spent three days away from home. My mother did what every good alcoholic would do – she got blotto to numb the pain of not knowing where I was or who I was with. Then my mother dropped a bomb shell bit of news on me the morning after I returned home. Thinking back now, the night before reminds me a lot of scenes straight out of a Hangover movie.

I remember sneaking up the short flight of stairs to our apartment on the second floor surprised that our apartment door was unlocked. Only now do I realize my mother must have left the door unlocked because she was worried about falling asleep and missing my arrival. My attempt to tiptoe down the hall to the bedroom I shared with my sister failed. She appeared out of the shadows, made a yelp of joy and proceeded to hug me until I begged to be released.

In the morning after she had several cups of coffee as I was tiptoeing around the kitchen getting breakfast, she called me into the living room. I expected to be met with tears and maybe even a bit of hysteria. At first, I ducked thinking she was going to hit me for running away. She didn’t hit me; instead, she started crying then grabbed me and held onto me as if she thought I was going to die. She rocked me in her arms for several minutes. I was surprised and embarrassed for the both of us.

Then she pointed at something on the coffee table and said, “I called your friend. She said you guys had been at Phalen Lake at a bonfire party and she’d gone home, and you stayed. You never called me. I’ve been worried sick about you all this time and you never called me. Listen to me Kelley, listen good. It’s important. You see those two on the front page there?” She was pointing at the tabloid magazine on the coffee table next to her cigarettes. “Go on. Read the article, just read the article and I’ll explain.”

The article had to do with a young married couple who’d had a baby and discovered they were sister and brother. Even back then I thought the tabloid magazines sold at the grocery store counters were a bunch of trash, only good for lining birdcages or scooping up dog poop. After reading a bit of it I threw the paper on the floor and turned to go back to the kitchen. She stopped me. “Where are you going? Come back here. Sit next to me. I have to tell you something very important.”

Knowing how persistent my mother could be I reluctantly sat down beside her. “I was in the Navy when I discovered I was pregnant with you. It was during the Navy’s swim test. You see we all had to jump off the high dive fully clothed. Can you believe it? We had to wear our shoes and all our clothes and swim across the pool to the other side. I managed to dive off and swim across the pool, but I felt sick to my stomach. The doctor who examined me told me I was pregnant. I was discharged from the Navy soon after and sent home.”

“Dah. So, what?” I said shrugging my shoulders. I was such a snot back then.

“It’s a big deal because the man you think is your father, well, I didn’t start dating him until you were six months old. I didn’t even know him until after you were born.”

“Okay then. Who’s my father?”

“I don’t know.”

“What? Are you kidding me?”

“Well, he could be the man who was my fiancé back then. We had a fight and he wanted to call off the marriage, so I threw my engagement ring in the snow and a few months later I joined the Navy.”

“Okay, what’s his name?” She told me his name and when I jerked away as if to jump up from the couch, she grabbed my wrist stopping me from fleeing the room. “Or. It might be the guy I’d been dating after the breakup.”

“What guy?” She told me his name. When I heard the name, I felt sick inside but said nothing at the time.

“Your grandpa threatened to shoot him if he didn’t pay for the hospital bill and he didn’t dispute the idea that you were his kid. He paid the lawyer and the hospital bill, but I still believe your father is my old fiancé, you have his curly red hair.”

“What about the other guy?”

“I think he’s Jewish. I remember when he took me over to his parent’s house there was one of those candle things, decorations in the window.” Later, I went to the library and looked up Jewish traditions during the holidays and realized she’d been talking about a menorah: a seven or nine candled lamp-stand made of gold used by the Jewish people to celebrate Hanukkah.

The only reason my mother brought up the true story of my parentage was because she’d read a sensationalized piece in her favorite tabloid paper. The headline caught her attention immediately and disturbed her greatly. At first, when she pointed at the tabloid, I thought she’d finally gone off the deep end – did she really think I was the offspring of some lizard alien disguised as a human? Then she showed me the tabloid and the page where the brother and sister were mentioned. Their pictures were also included with the article.

It was a relief to see human faces on the page and learn the article referenced newlyweds who discovered they were brother and sister. I vaguely recall the picture of the young wife and her young husband and the wife holding their baby, if the baby was really theirs or not. The interesting part I never considered until now is the question of whether the young people might have been from South America. Would the tabloid dare print a sensationalized story about a young white American couple who got married not knowing they were brother and sister? I don’t think so, knowing what everyone knows about that tabloid’s dubious tales.

So, after reading that piece of garbage called a magazine, my mother feared I might end up marrying my brother one day? Had that been her compelling reason for finally telling me the truth about my parentage? The world is a wacky goofy place and family secrets can be the wackiest and the goofiest. I recall vividly her concern and the urgency in her voice when she warned me to be careful when choosing a husband, just in case I might inadvertently marry my brother.

“What’s the guy’s name?” I asked. “The one that paid the hospital bill?”

She told me his name, again. “But I’m sure he isn’t your father. You have (blank’s) green eyes and red curly hair. I just know (blank) is your father.”

So, why did I decide that the other guy, the one who didn’t have red curly hair, must be my father? Was my choice based on instinct or the romance of being an outsider? Maybe a little of both. Maybe I wanted to be a descendant of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Or maybe being the daughter of a Jew explained the reason for my impressively sized nose? Mostly I think my reason for choosing Sperm Donor No. 2 had more to do with my admiration for the tenacity and strength of the Jewish people, how they overcame hostility, prejudice, and The Holocaust to create their own place in the world.

After all, in those days, the early 1970s, the end of World War II was still fresh in people’s minds – less than thirty years had passed. Numerous books had been written about the struggle of the Jewish people to reclaim Israel as their homeland, and how so many had been killed by the Nazis and how they survived the Holocaust. I still recall watching the movie based on Anne Frank’s life on television and later news programs feeding us information about the Munich Olympics on September 5, 1972.

Before my mother’s bombshell announcement, my favorite television series, which I watched with my mother was based on the bravery of American soldiers during World War II, entitled Combat! I also watched Judgement at Nuremberg with Spencer Tracy in a key role on multiple occasions throughout my teen and adult years. Later, I would discover books written by Leon Uris and devour them throughout my early adulthood. There wasn’t a year that passed in which a new revelation about the bravery of British, Russian and American soldiers wasn’t dramatized in movies, books, and television programs.

By the time I met my fifth father in the early 1980s, I’d firmly settled on Sperm Donor No. 2 as my biological father. And when my fifth father, newly married to my mother compared me to Barbara Streisand, the compliment reinforced the story told to me by my mother. Even knowing today what I know about my heritage, I’m still flattered to be compared to Streisand; I just wish I had as lovely a voice as she. Years later, a friend-with-benefits relationship after my second divorce resulted in a taste of what it’s like to be on the receiving end of antisemitism, nothing like other Jewish people endure but still painful. Let’s call this friend-with-benefits Chuck.

Chuck happened to be a member of our bowling league. A few months after we’d started our odd relationship Chuck invited his friend from New York to the tournament where we were competing against other bowling leagues. These leagues were made up of working-class people, many of them in the construction business: hardworking plumbers, electricians and carpenters.

Bowling as a sport or a game or whatever it is, to this day, I love to watch but hate to play. I played on an all-female bowling team sponsored by my favorite watering-hole where I spent a lot of evenings trying to talk over the other drunken people in the room. The bar owner paid for our bowling jackets which advertised her bar. I was a terrible bowler but had a high handicap. The ladies put up with me because when I had a good night, my handicap improved the team’s overall score.

Toward the end of the night Chuck introduced me to his friend from New York. I can’t even remember his friend’s name or what he looked like; I’d been very drunk at the time and the place was noisy. The next day, I heard the slur second-hand by way of Chuck’s uncensored mouth. Without a second thought, he repeated his friend’s slur with a sangfroid attitude, a cluelessness which symbolized our tawdry relationship. His friend from New York warned him to, “Watch out for that Jewish Princess; she’ll make your life miserable.”

I suspect Chuck repeated his friend’s slur as his way of warning me to keep my distance, maybe his feeble precursor to a breakup. We weren’t dating, so I’m still not clear what he thought he was accomplishing. Although, maybe he thought I was falling in love with him, since he was a rebound after my divorce? I confess for a short time I did think I was in love with him, until my company Christmas Party when I wished I’d never invited him and realized I wasn’t in love with him after all, since he’d embarrassed me in front of my boss and my coworkers.

Oddly, my mixed reaction to the slur still surprises me today. I was thrilled to have another person identify me as Jewish and compliment me with the moniker “Jewish Princess.” I’d always wanted to be a Jewish Princess. Yet, I was insulted that his friend warned him to stay clear of me. Then again, a Jewish Princess meant I thought of myself as royalty and would make demands upon a man expecting only the best. Now that I think on this definition, I must confess looking back on past relationships, that I have been a bit of a high-maintenance wife and girlfriend at times. Why not? It’s better than permitting a husband or boyfriend to treat you like a drudge only good enough to bare children and cook his meals.

In my lifetime plenty of people have commented on my appearance, some comments were rude, some thoughtful, others critical and a few murky with a hint of condescension. When we were kids, my half-sisters enjoyed pointing out the obvious by saying, “You have a big nose.” Back when they were children, they could be excused for being little snots; unfortunately, the bullying didn’t stop when they reached maturity. I believe their insults stemmed from an awareness, at an instinctual level, that we didn’t share the same father. My half-sisters aren’t stupid, far from it. They just didn’t know all the facts and maybe they came up with their own conclusions, like my former boss who made an unsolicited remark about my appearance by telling me, “You’re not beautiful but you’re striking.”

I’ve noticed these appearance-critics tend to jump to conclusions and thereby betray their inborn prejudices. The descriptor of “Jewish Princess” or “big nose” or “striking” are passive-aggressive comparisons the fearful use to distance themselves from what they perceive to be the other, often as a way of demeaning those that they fear. What I find marvelous is that the discovery of DNA now exposes these critics as lazy or intellectually challenged or even worse, racists. I managed to survive the nightmare that is called high school, so by the time these remarks had been made, I’d had years to prepare and protect myself from their overt, but more often covert attacks.

At least now Americans are discussing racism and antisemitism. The lingering annoyance of the “male gaze” though, that cruelty still survives in our courts and in daily life. We, females, forced to attend public schools, who managed in one way or another to survive the life of unwilling participants in everyday beauty pageants, our bodies and faces constantly judged, rated, and belittled throughout our formative years, now realize the pageant never ends. It’s still something women endure every day in our modern world. No wonder American women are traumatized by the election of POTUS #45, he’s a reminder of our treatment by the immature male brain.

In the past, people (thinking they were being helpful) suggested medical solutions for my “striking” appearance. But I’d already decided long ago not to use modern medicine to change my face. Why would I survive those traumatic teenage years filled with insults about my nose and then give in and pay for plastic surgery? I owe Barbara Streisand a debt of gratitude for my decision to never have rhinoplasty. She refused to have her nose fixed for fear of losing her voice. Her story and her resolve strengthened my determination never to let the critics make me do something I would regret later in life.

So, there I was graduated from high school knowing the name on my birth certificate wasn’t my biological father’s name. Did I go in search of him? No. Why would I, back in 1972 DNA testing hadn’t been offered to the public yet and HLA testing was inconclusive? Besides, I had other things on my mind, a new husband, a new baby, a trip to Oregon and a chance to go to college. But before life got in the way of my search for my biological father, I did a bit of snooping around the apartment hoping my mother might have left some sort of clue.

Like Victoria Winters, I was intrigued with Dark Shadows’ Collingwood because I too wanted to know more about my origins. I knew the man I called Father couldn’t be my father. I looked nothing like him, and my sisters looked nothing like me. So, like Victoria Winters I went snooping in my mother’s bureau and found some interesting documents. But those documents had nothing to do with me. My search to learn who my biological father might be, began in 1972, then went on hiatus for forty-three years, reawakening in 2015 when I paid for a DNA test through Family Tree DNA. My suspicions have since been confirmed with the research I’ve done on the Internet and on Facebook.

Forced to delve into the reasons for my attraction to the 1960s Dark Shadows’ television series when I was a young girl and uncovering a bit of the real story through DNA testing, I’ve also set aside the family mythology my mother and others force-fed us for decades. The idiotic story that our family had a Native American ancestor had been crammed into our immature noggins through repetition and self-congratulations, by not just my mother, but a distant relative who self-published a book based on her dubious research.

The lie was firmly rooted in my mother’s brain from the flimsiest of evidence when some idiotic-lounge-lizard asked her what tribe she was from, probably because she had straight black hair, brown eyes, a summer tan and a friend sitting next to her who happened to be a real Native American. Then through repetition and embellishment over decades everyone in the family began to believe the lie. And just like the serial liar in the White House today, repeating lies allows the feeble-minded to suspend their disbelief and accept the lie as truth.

The lie has had mixed results for subsequent generations in my family. My eldest son went so far as to enlist the services of a Native American to teach him the culture of his people. If he reads this piece, I hope he concludes that even though he may not be Native American, learning the culture and spiritual practices of Native Americans is an improvement over the education he might have gotten from some racist group.

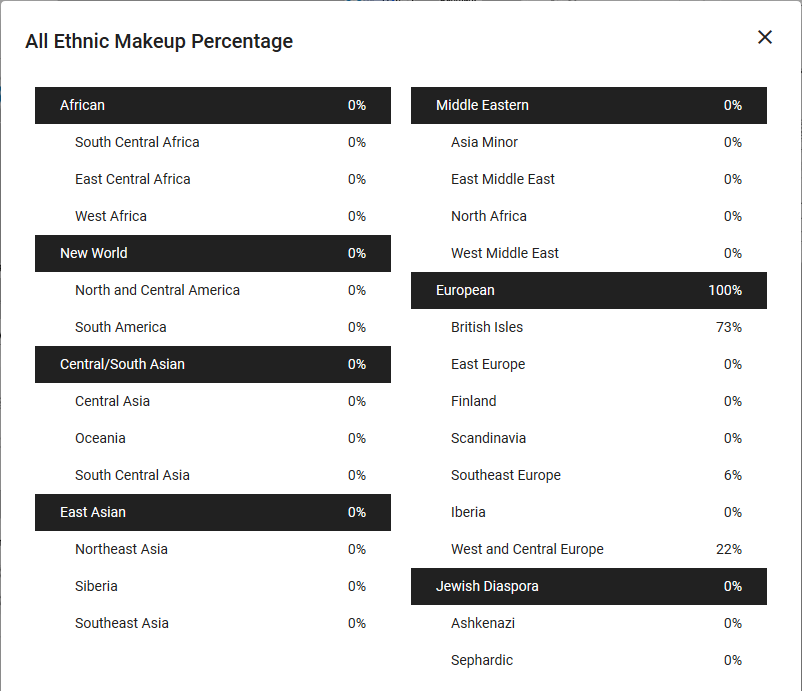

After spending years reading Leon Uris’s books about the founding of Israel, believing myself to be of Ashkenazi descent based on my mother’s brief glimpse of a holiday decoration, then as a teenager dreaming of flying jets for the Israeli Army, giving that dream up when I learned I would have to have math skills, and then only years later to realize I’m 100% European with 73% British Isles, 22% West & Central European and finally 6% Southeast European (think Greece and Italy), I can only conclude my mother mistook a Scottish holiday wreath for a menorah. The holiday decoration could have been a yule log with candles.

Also, I realize now how for decades I’ve suppressed the truth from even myself. I’ve never bothered to question her story about throwing the ring given to her by that former fiancé into the snow and the date of my birth.

In 1972, a few of my concerns about why I felt like an outsider in my own family were finally answered. Yet, I still wanted to know more, wanted to learn more about my biological father. Most of my life the man I thought was my father turned out to be no such thing, a man who was absent even when present. Now, I’m beginning to understand why he ignored my overtures of childish affection, wrote to me as if writing to a stranger (which we were essentially) and felt betrayed when my mother revealed the truth.

Even when I became a young mother after he was released from prison and while he was living in Arizona, our relationship was strained. I felt uncomfortable around him and he treated me like the stranger I had become. Years later, after he died, my mother told me she’d made a pact with him and how upset he was when he learned she’d told me the truth about my parentage.

What difference did the truth make to him? He was never around when we were growing up? Between stints in jail, he was off living his life with his friends and new girlfriend, so why did he feel my mother had betrayed him by telling me the truth? A memory from my childhood may explain why he felt betrayed.

My mother used to tell me how he was the only person who could get me to fall asleep when I was a baby. She said he would pat my back for hours and talk to me in his deep baritone voice. To this day, the feature I find most attractive about a man is his voice. The man who adopted me, my first father, the one who taught me how to tie my shoes, he imprinted himself into my psyche in a way no piece of paper could ever legitimize. Even though he left us many times and even though he wasn’t my biological father, I still consider him to be my first father.

Still.

Learning I wasn’t the bank robber’s biological daughter worked out in my favor in the end. At first, the knowledge that he wasn’t my “real” father hurt a lot. Then as I got used to the idea, I still felt jealous that he loved his biological children more. But all the while, I was creating an image of my “real” father, sometimes romanticizing the idea of him. Knowing the truth about my parentage ended up being a win for me. Not at first though. No. It took years before I realized how much the truth would influence my life – in so many good ways.

It is sad to think my mother died before I could tell her that she’d been totally wrong about her former fiancé. He wasn’t my “real” father. After my investigation, the man she refused to believe was my father turned out to be the sperm donor indeed. Now, I wonder if she ignored the evidence because she really wanted her former fiancé to be my father, the fiancé who spurned her.

Even though my mother was the least prejudiced person I know, another reason she might have preferred the French Canadian to the man with the big nose could have been because she didn’t want me to be Jewish. She needn’t have worried. I think she would have been delighted to learn the truth about my DNA test, but when I got the results expecting to have a bit of Native American ancestry and a bit of Ashkenazi ancestry, my reaction was shock and dismay. For most of my life, minus sixteen years, I’d come to believe I had Jewish ancestry in my family tree. That was not the case.

Anyway, my search for my biological father started the day of the garbage-tabloid article which led to my mother’s confession about my origins. Eventually though, I soured on the idea of finding my father when I learned Grandpa Shorty had threatened to shoot the man if he didn’t do his duty by paying for the hospital bill. All those years living in the same town as my biological father and he knew he had a daughter by my mother and never tried to get in touch with me. That knowledge hurt, hurt a great deal. When we left the state where I was born, I gradually lost interest in finding my biological father, even when testing for paternity became the rage. I wasn’t even interested decades later when DNA testing became so popular.

I no longer do the mental gymnastics of what-if, because after my DNA test, over the years, I have learned how precious the sequence of events turned out to be, they created the person I am today. What I am most proud of is that I am an open-minded person with a curiosity and appreciation for all sentient beings on this planet. If I had known from the very beginning that my biological father was of Scottish descent, would I be the person I am today? Would I be the kind of person who loves it when people mistake me for a Jewish Princess?

Would I feel as passionate about social justice issues today if I had known from the beginning about my European ancestry? Maybe. I’m glad I only learned the truth, after spending more than half my life believing I had a bit of Jewish ancestry mixed in with the European.